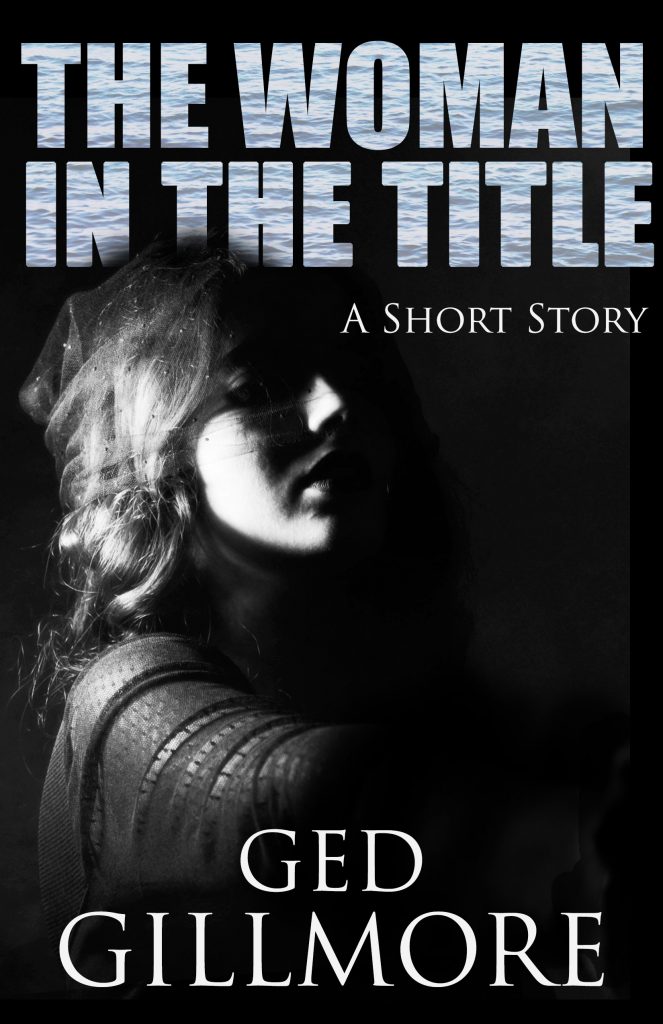

THE WOMAN IN THE TITLE

An exclusive short story featuring Bill Murdoch, the world’s most reluctant private investigator.

Murder’s just a word you read in the papers until it happens in the same room as you. After that it’s blood, forever muddy in your nostrils; the twisted body, small and heavy, whenever you close your eyes.

Murdoch saw her first in the meat section, struggling over cuts of steak. Outside it was autumn, the air gentler than it had been in months. People kept telling Murdoch it was a wonderful season, until he realised every one of them had forgotten his grief. Or, worse, maybe they thought the weather could fix it? Coles in Crosley was meant as an escape, the last place anyone in love with the day would choose to spend it. But vinegar, oven cleaner, chickpeas, Chux: none of them made him feel better. Forcing his trolley onward, he saw the woman again at the freezers and wondered what it was about her that made him want to stare. Dark jeans and a black t-shirt implied a good body, a great body for her age, but that wasn’t so unusual on the Coast. Her cropped hair was expensive, this year’s mix of moneyed colours, but when she looked up without warning – Murdoch blushing and turning away – her brown eyes were just brown eyes. Nothing to explain his acute awareness of her progress up and down the aisles, then slowly through the checkout queue two along from his own. When he emerged blinking into the carpark, he found himself wondering where she was.

‘Are you Bill Murdoch?’

She was close, in sunglasses, her perfume denying the surroundings. One hand on his forearm, in the other, a tidy bag of shopping that mocked his trolley where the toilet rolls were uppermost and waving. Murdoch left off managing his car keys and fumbled for his sunglasses instead.

‘Sorry, love. Do I know you?’

Later, of course, there were fifteen better things he could have said. It was a game that tortured him, the missed opportunities. Behind her, across the carpark, the highway was heavy with traffic, a proudly polluted river, but the woman’s next question was as quiet as her first.

‘Can we talk in my car, darl? It’s just over here.’

She turned and walked that walk towards the shade of the awnings, taking a wide arc to let a four-by-four reverse painfully across both lanes. The driver smiled and raised a hand, thanking Murdoch for his wife’s patience. Murdoch scowled and looked away.

Her pristine white Holden was parked only three cars from his Merc. Murdoch told the woman to hang on, beeped his car open and lifted his shopping into the boot. Not showing off the car, for once, not even gaining a semblance of control. Just keen to be free of the toilet rolls. He felt her watching him over the metal roofs and, once done, wheeled the trolley up to the trolley bay and inserted it firmly into the others waiting there. Like that was the kind of bloke he was: a solid upstanding citizen. They were inside the Holden, her scent struggling against the plastic interior, before either of them spoke again.

‘New motor?’

‘Yeah.’ In here her voice was more confident, deeper than he’d noticed. ‘I only bought it a week ago.’

She was lying. It was a hire car, he’d recognised the little sticker on the back rego. She told him her name was Cathy Taylor, then turned in her seat to offer a polite hand, the flesh of her fingers pressing his palm for such a tiny moment longer than necessary that he decided he’d imagined it. He sat uncomfortably, cursing his shorts, the pale of his legs pressed out by the hot plastic of her passenger seat.

‘Sorry for grabbing you in the carpark,’ she said. ‘I didn’t want to come to your office but. I want to hire you, see, except… we never met, yeah?’

He’d been in Australia long enough to recognise a country accent. ‘Country’ being how the locals’ said ‘working-class’ without feeling like the snobs they were. The woman was waiting for an answer, so Murdoch said, yeah, course love, no problem at all. Whatever she wanted to hear.

‘See, the thing is Bill, I’m being blackmailed. This bloke keeps calling me up, says he’s going to tell people things I don’t want them to know.’ She remembered she was wearing sunglasses, pulled them off and gave him her brown eyes; managed that for less than a second before looking at her hands instead. ‘What I want you to do is find out who this man is and where he lives. Then go round and tell him to stop. Nothing violent, don’t get me wrong. But I reckon once he knows I know who he is, and where he is and that, it might be enough.’

Outside the window behind her, a white-haired man had climbed into his car and was now reversing slowly, the stage set rolled away before the scene was done. The woman checked her watch and asked Murdoch if he’d take the job.

‘Blackmailed for what?’

‘That’s not important.’ Her hands fluttered near him, knee and forearm, but decided not to land. ‘Something from a long time ago. Nothing what would help you find him.’

She gave a firmly apologetic smile, told him what the rates on his website were, how much she’d pay in advance. It was in cash in the glovebox, nothing else in there but the logbook. Once he had the money in his hands, she relaxed; a smile with teeth this time, hands back under control. When he made a joke she laughed and their eyes locked for a second. She took him through the details: a land line number from the first Friday night the blackmailer had called; ‘No Caller ID’ every time since then. She thought he’d called from a pub, maybe someone in the background had called him John? Accent, time of day, number of calls; nothing useful. They shook hands again, longer this time. Now or never.

‘Maybe we could have a drink?’

‘Later,’ she said, so quickly he knew she’d thought about it too. ‘Once this is over and done. Keep things tidy, you know?’

He knew. He was in the Merc, the cash in a new glovebox, seatbelt on, air con on, about to turn the key, when she appeared outside the passenger window. Nerves nibbling at her bottom lip, hands pressing against her jeans. It was the eyes after all, the way she smiled with them first, her lips only catching on slowly. He reached over and opened the passenger door.

——————–

The sex was unbridled, the effort of pushing and pulling to a common middle ground a good part of its own reward. But later, no matter what she had given of herself physically, she shared no more than she had done in the car. She spoke of everything but herself, evading his questions so gently that to insist would have been brutish. He, on the other hand, had to explain everything. The lack of music on his phone when she asked if she could play a song; his bare bedroom walls; the books beside his bed.

‘Don’t tell me detectives read detective stories!’ She was face down, head and shoulders hidden over the edge of the mattress as she pushed naked through the paperbacks on the floor. ‘Don’t they annoy you? You know, being so different from how things really are?’

‘So what do you read, then?’

He hadn’t meant to sound like he was searching for clues.

‘Oh, you know.’ Aw yin now. ‘Same as everyone else. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, The Girl in the Ice. Anything with ‘girl’ in the title so we can be sure there’s gonna be suffering. Never ‘woman’, you notice.’

She stopped herself and he listened to her rearranging the books. Asking would only weaken what little he had. Instead, he traced a hand down the back of her thigh and let it rest behind her knee. If she bore any scars of whatever it was, they weren’t physical; he’d looked closely enough to be sure of that.

She kissed him hard when they arrived back in the dark and still busy supermarket carpark, one hand on the back of his neck like there was something she needed to tell him. Then, with no goodbye, the car was suddenly empty around him. He wanted to call her back, regretted having showered, anything to keep something of her. But she’d made him promise, promise, not to try and make contact. She’d be in touch for an update. He followed the line of traffic around the edge of the carpark and, when he looped round past again, she was in her car, her features silhouetted by the brightness of a phone against her ear.

——————–

Twice that night, and three times the next day, he called the land line the blackmailer had used. He let it ring for so long as to be aggressive, an arsehole in the traffic leaning on his horn. But no one was provoked to pick up. Eventually he called Davie instead.

‘Mate, that wanker you know what works at Telstra, said he’d do us a favour for a ton a pop. What’s his name?’

‘Better,’ said Davie. ‘Thanks for asking. Still in bed though. You?’

‘Sorry, mate, how’s the man-cold?’

‘Flu!’ Davie coughed for proof. ‘It’s the flu. Killed more people than the First World War, did you know that?’

Murdoch said nothing. The more ridiculous Davie’s facts sounded, the more Google tended to agree with him. There was another cough and a rustle of sheets.

‘Warwick.’ Davie sounded like he was gargling. ‘You talk to him though, I’m too sick.’

Murdoch took down the number and said yeah, sure, don’t worry about it, get well soon. Mate. Like he’d ever have let Davie do it.

——————–

The address was in Surry Hills, squeezed among the million-dollar workers’ cottages. Arriving there at ten, Murdoch was inspired to stay in the car and stare at it through his windscreen. It had rained all night, the forecast a joke, the slow light revealing a saturated day, pavements treacherous with wet leaves. Anyone could see what kind of place it was. Half see at least, that was the point of the awning that hid the front door. He sat for a long time not knowing what to do, passers-by too concerned with staying dry to notice a man in a car. At lunch-time there was movement, three tiny women on the way out, each of them hunched under a fragile umbrella, on flat shoes not made for the rain. Half an hour later, a BMW parked lazily in the loading zone outside the front door. The man it produced was tall and middle aged, too confident to worry about his weight apparently, but not above some bling at the wrist. He had skin like a drinker, dark hair pushed back from a smooth brow, something cruel about the mouth. He was into the place and out again in less than ten minutes, no shame about him as he took off without checking his blind spot. Murdoch got out and hurried across the road.

He’d expected a bell or an intercom, a check by a camera before they let him in, but the door was open, a blur of radio competing with the wet street noise behind him. Inside was a gloomy reception area, gilt and mirrors sad they had nothing to reflect. There were a few seats, a few naked pictures on the walls. Other than that, just a tall veneer reception desk, beside it an arched entrance to a dark corridor. Behind the desk, a mirrored door was open to an office, piles of paper and too much furniture, the radio in there somewhere, rabbiting away in Chinese. Someone had been cleaning the floor, the whole place stank of bleach.

‘Hello?’

Nothing. Murdoch took out his mobile and dialled the landline number. Within seconds a harsh phone was drowning out the radio. He leant across the reception desk to see if he could spot it, but on the shallow shelf behind there were only business cards and pamphlets. He had just pocketed one of each when a woman appeared in the arch to the right of the desk. She was short and puffy-faced, cheeks spreading unevenly around her tiny mouth and tired eyes. She had a dustpan in one hand, loose papers in the other.

‘We closed,’ she said over the noise of the phone. ‘Nine o’clock in night you come back.’

‘I’m looking for the boss,’ he said. ‘Is he here?’

‘You miss him.’

She shuffled towards him desk, her feet in oversized slippers, pink gormless rabbits dragging her pebble-dashed legs.

‘You go!’ She held the dustpan and papers out wide, maximising her size to intimidate a predator. ‘Closed!’

‘But I want to give you two hundred dollars.’

She didn’t hear him so he took it from his pocket and held it in the air between them, his weapon against hers.

‘You answer one question and I give you two hundred dollars. Then I go and never come back.’

She frowned and looked back down the corridor, then to the door to the street. Noticing, for the first time, this was open, she shuffled over and kicked it shut, the smell of bleach immediately stronger, the phone in the office louder. She turned, hands on hips, and waited.

‘Who uses that phone?’ said Murdoch, pointing. ‘Who makes calls from the office?’

She frowned again, so he pocketed the cash, held out his fingers and clicked them, killing the call in his other hand at exactly the same time. It was a cheap trick but she liked it. Then she remembered his offer and frowned again.

‘You go,’ she said quietly.

‘In ten seconds I go and you have two hundred dollars. Who uses that phone?’

‘Mr Tony.’

‘Mr Tony and who else? Who uses it on a Friday night?’

‘You go now.’ It was the corridor that bothered her, not the door to the street.

‘A man comes in here on a Friday and he uses that phone. Who is he?’

He brought out the money again.

‘Mr Johnny.’ It was a confession, eyes everywhere but on him.

‘He’s the boss is he?’

‘No! Mr Tony boss. Mr Johnny old boss, maybe they business partner, I dunno.’ She saw something in the corridor and raised her voice. ‘We closed! You go! You go now!’

Murdoch turned. The world’s oldest teenager had appeared under the arch. Hollow cheeked and transparent, she was holding a broom like it was made of lead. She gave him a look like a plea for help, then turned and disappeared back into the shadows.

——————–

The business card from the reception desk called the place Cristel’s, no match. But the pamphlet called it Babylon and matched the address for Backstreet Babylon on the Australian Business Register. Clicking through, Murdoch found JONATHAN TELLEMANN INVESTMENTS and offers to purchase the company extracts: Change to Company Details Member Name or Address (484A2) and Change to Company Details Registered Address (484B). Nineteen dollars each. He decided to save the money, seeing as the Address for Service of Documents was provided. God help private detectives the day anyone else discovered the internet.

——————–

Sawmill Road was back in Crosley, one of the single-story streets behind the racecourse. Number fifteen wasn’t much shabbier than its neighbours; you had to sit in a car across the road for an hour before you started noticing the difference. Rubbish bin left out; grass unmown; letterbox stuffed with junk. Catching on at last, Murdoch swore and peeled himself out of his seat, the back of his legs happier outside the car. Amongst the ‘To The Householder’ junk he found two letters addressed to J. Telleman. He rang the doorbell, banged on the door, poked around the backyard. Back to the Merc. Twenty minutes later his ring tone woke him, light rain on the windscreen, the phone on the floor of the car somewhere. He scrambled around at his feet swearing until he found the handset trembling under the brake like a baby bird.

‘Hello?’

‘Bill, it’s me. Any progress?’

He was still in the half-reality of waking, her voice like something he’d dreamt. Suddenly self-conscious, he looked down to find he’d drooled a stain across his shirt. He covered it with his free hand.

‘Yeah, good progress, actually. I think I might have found your man. Sitting outside his place right now.’

‘Fair dinkum? What’s the address?’

He told her and heard something change.

‘Hang on a second, Bill.’ It was more than a second. It was a muted three minutes and a different tone of voice when she came back on the line. ‘Bill, I’m sorry, darl, but I don’t want you to do anything else. Sorry to muck you around but it’s off. I can’t explain, I just need you to trust me.’

‘You what? But…’

‘No, Bill, seriously. Case over. The money I gave you covered a week’s work and it’s only been two days. So we’re quits, eh? Promise me you’ll leave it. Promise? Say you promise.’

After a few minutes of back and forth, she got the word she wanted. Murdoch drove around the block, like he needed to believe it himself, then parked back where he’d spent the previous hour or so. As he waited, the rain grew more serious, a thousand tiny explosions between the wipers, the rest of the world a blur. After twenty minutes, when he thought he saw a figure entering number fifteen, he had to wind down the window, bare face to the needles to be sure.

The man who answered the door was done in. Booze, fags, smack; all of the above. Small and grey, even for his age, his narrow shoulders crowded his ears like he was still out in the rain. He smelled of beer.

‘Mr Telleman?’

‘Yeah? What do you want?’

Murdoch pushed past him into the dimly lit house. In the front room, the furniture had been expensive once, then vintage, now worthless. A black ring surrounded a hole in the carpet near the gas fire. Behind him, the old man repeated the question, then swore and shut the front door.

‘Take what you want,’ he spat, following Murdoch into the room. ‘Fucking debt collectors. Take it all. If you can find anything worth flogging.’

‘You don’t live very fancy for a man what owns a brothel.’

Telleman looked at him like he was mad. Then the old man seemed to remember he still had his raincoat on, the shoulders dark with damp. He took the coat off and threw it towards the sofa, where it landed badly, arms askew like a corpse.

‘Sorry to disappoint you, son, but I don’t have nothing. No cash in the house, no money in the bank. Just spent the week’s pension down the pub.’

‘You’ve got Babylon.’

Again the uncomprehending stare, black dot eyes deep behind the skin.

‘The brothel down in Surry Hills?’ Murdoch tried. ‘Cristel’s?’

Now Telleman got it. He laughed an ancient creaking laugh, disconcerting gaps between his teeth. Then he gave a sudden frown. ‘You the tax man or something?’

Murdoch asked him if he looked like a fucking tax man. The old man nodded agreement that he didn’t, pushed past him, crouched down and punched the gas fire into life. There was no fear in him at all.

‘Tony Andreotti’s a mate of mine,’ he said over his shoulder. ‘Used to do a bit of business together. My name’s on the docs, some reason I can’t remember. He helps me out now and then, free fucks and that.’

A brassy chime from the hallway and the old man sighed and stood again.

‘Fucking George Street on a Saturday,’ he said. ‘This gonna be a mate of yours, case you can’t manage me by yourself?’

He returned from the hallway walking backwards, hands raised in the air as far as his skinny arms would allow. Then came Cathy Taylor, like something out of the movies, headscarf tight around her face, a neat little Beretta in her hand. If she was surprised to see Murdoch she didn’t show it.

‘You promised,’ she said.

‘Cathy, what the hell…’

Telleman turned and gave him that stare again. ‘What you calling her Cathy for? Her name’s…’

The report from the Beretta filled the room, its higher reaches stinging Murdoch’s eardrums, the rest a punch in the stomach. Telleman lay twisted, mouth and eyes open, blood pumping steadily from a hole near his heart. Behind him the room was spattered. Murdoch found his own mouth open too, as much use as the old man’s. Cathy Taylor was doing the talking.

‘Are you listening? I tried to get you to stay away, but you wouldn’t.’

‘You… you…’

‘Yeah, I killed him. He deserved it. He was an animal, always was an animal. Drove my mum to suicide, raped me a few times till I got me and my sister out of there. Then last month he turns up, threatening to tell everyone I was on the game for him and Papa Tony. So yeah, I killed him and I’m glad of it.’

She didn’t look glad of it. She looked like she was deciding whether to vomit or faint.

‘I don’t want any part of this,’ Murdoch told her. His voice sounded distant even to him, no different from the ringing in his ears.

Cathy Taylor was still staring at the body. ‘Yeah, well,’ she said. ‘I don’t want you to be any part of it neither, darl. And I’m very sorry, but, just in case, this gun was bought by a man with an Pommie accent who looks a bit like you. And, don’t forget, your car’s the one’s been outside for hours. And you’s the one been asking around for him. So, don’t come after me, and I won’t point anyone at you. Promise.’

‘You expect me to believe that?’

He didn’t care if she did. The plan had been to record Telleman confessing to the blackmail, the phone was still recording in his pocket. She gave him the same apologetic smile as in the supermarket carpark, although it didn’t seem to come to her easily.

‘You don’t have a choice, darl,’ she said, grimly. ‘What you going to say? A woman did it and ran away? What woman would that be? No name, no car, no phone number, no meeting in your office. Let’s leave each other out of it, eh?’

‘Did you plan the sex too?’

She was unraveling, eyes wide, a glistening sheen rising through her features; she needed a minute before she remembered his question.

‘The sex? Don’t pull that one on me, Bill. Just because we connected in the sack, doesn’t mean it was anything more than that. Men have been pretending since time began that a root was the start of a beautiful relationship.’

‘And two wrongs make a right do they?’ He watched her think about it, staring at the old man still oozing onto the floor. ‘Do they, Cathy? Do two wrongs make a right?’

An energy was shaking her from within. Murdoch couldn’t tell if it was from a desperate need to believe that, yes, it was true about the wrongs and the rights. Or from the joy of knowing it was.

THE END